|

|

|

|

|

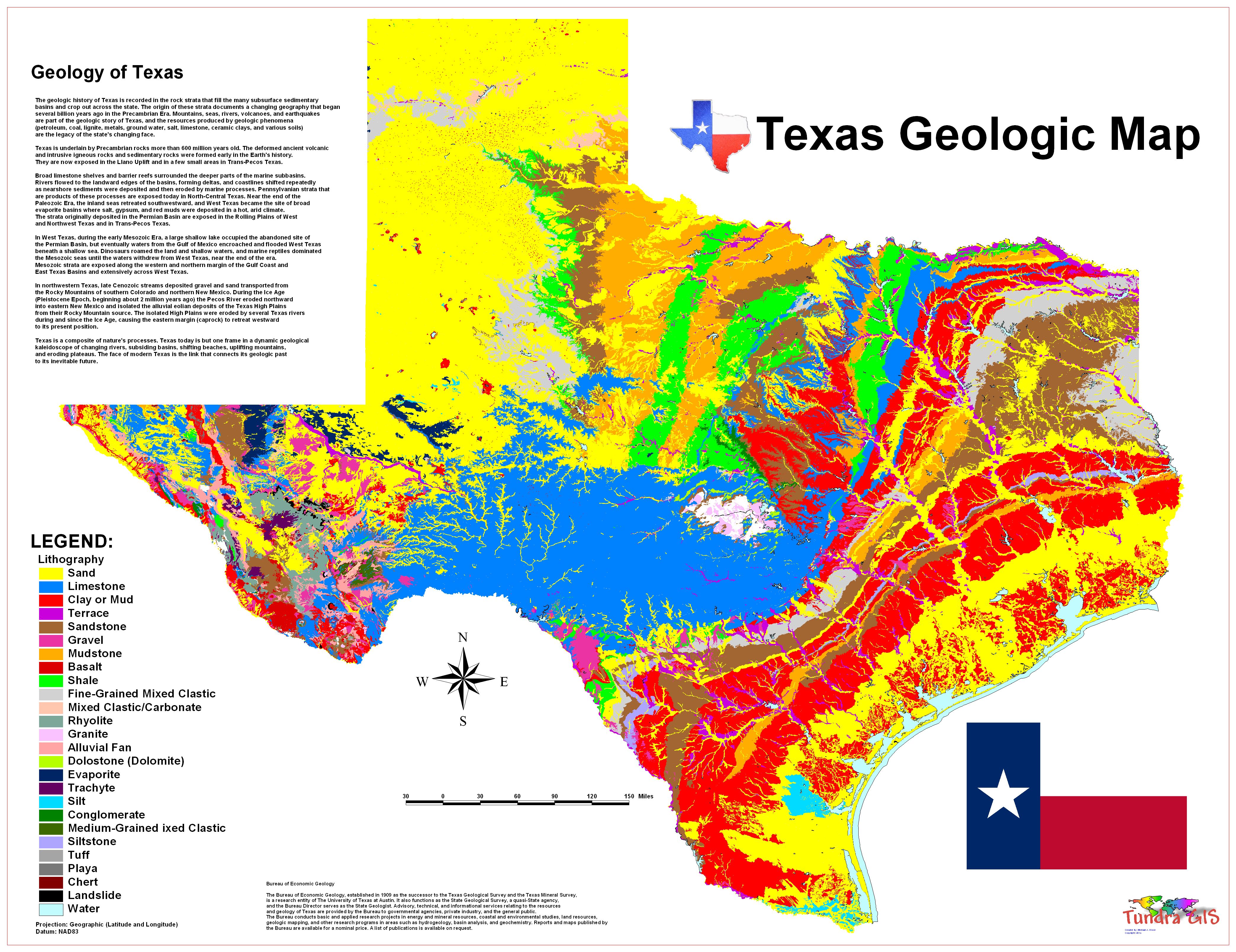

| Map Gallery Slide Show | Image 45 of 75 | Texas Geologic Map |

|

||

| Texas Geologic Map | ||

This map shows the geology of The State of Texas. Texas contains a great variety of geologic settings. The state's stratigraphy has been largely influenced by marine transgressive-regressive cycles during the Phanerozoic, with a lesser but still significant contribution from late Cenozoic tectonic activity, as well as the remnants of a Paleozoic mountain range. General geology Texas is approximately bisected by a series of faults that trend southwest to northeast across the state, from the area of Uvalde to Texarkana. South and east of these faults, the surface exposures consist mostly of Cenozoic sandstone and shale strata that grow progressively younger toward the coast, indicative of a regression that has continued from the late Mesozoic to the present. The coastal plain is underlaid by salt domes that are responsible for many of the oil traps in the region. North and west of the faults are the Stockton, Edwards, and Comanche plateaux; these define a crustal block that was upthrown during the Neogene. This large region of central Texas, which extends from Brewster County east to Bexar, and northeast to the Red River features extensive Cretaceous shale and limestone outcrops. The limestone in particular is important, both economically for its use in cement manufacture and as a building material, as well as practically; a porous limestone formation in the Texas Hill Country is the reservoir of the Edwards Aquifer, a vital water source to millions. Almost in the center of these Cretaceous rocks is the Llano Uplift, a geologic dome of Precambrian gneiss, schist, and granite, surrounded by Paleozoic sedimentary rocks. The granite here is quarried for construction, but it is perhaps best known to Texans through its manifestation as Enchanted Rock. From San Saba north to Childress, and from Wichita Falls in the east to Big Spring in the west, the surface consists of late Paleozoic (Pennsylvanian) to early Mesozoic (Triassic) marine sediments. These strata grow younger from east to west, until they are overlain unconformably by terrigenous Ogallala sediments of Miocene and Pliocene age. These late Cenozoic deposits dominate the Texas Panhandle. The geology of west Texas is arguably the state's most complex, with a mix of exposed Cretaceous and Pennsylvanian strata, overlain by Quaternary conglomerates. A series of faults trend southeast to northwest across the region, from Big Bend to El Paso; there are also extensive volcanic deposits. The Marathon Mountains northeast of Big Bend National Park have long been of special interest to geologists; they are the folded and eroded remains of an ancient mountain range, created in the same orogeny that formed the Ouachita and Appalachian Mountains. Texas has been one of the leading states in petroleum production since discovery of the Spindletop oil field in 1901. The state also produces uranium. In past years, the state has also produced mercury, silver, and copper. |

||

|

This map was

created for use in other projects as well as demonstrate GIS and

graphics capability. What is a Geologic Map? CLICK HERE TO DOWNLOAD |

||

| < back | up ^ | next > |